By Professor Ramakumar

It is not always that you say, "the end of an era". But the passing away of Professor Amiya Kumar Bagchi (Amiyada to me) is such an occasion. He was a towering Marxist economist from the "Global South" in the 20th and 21st centuries. The sheer sweep of his work and the enormous depth he brought to his analysis were simply outstanding.

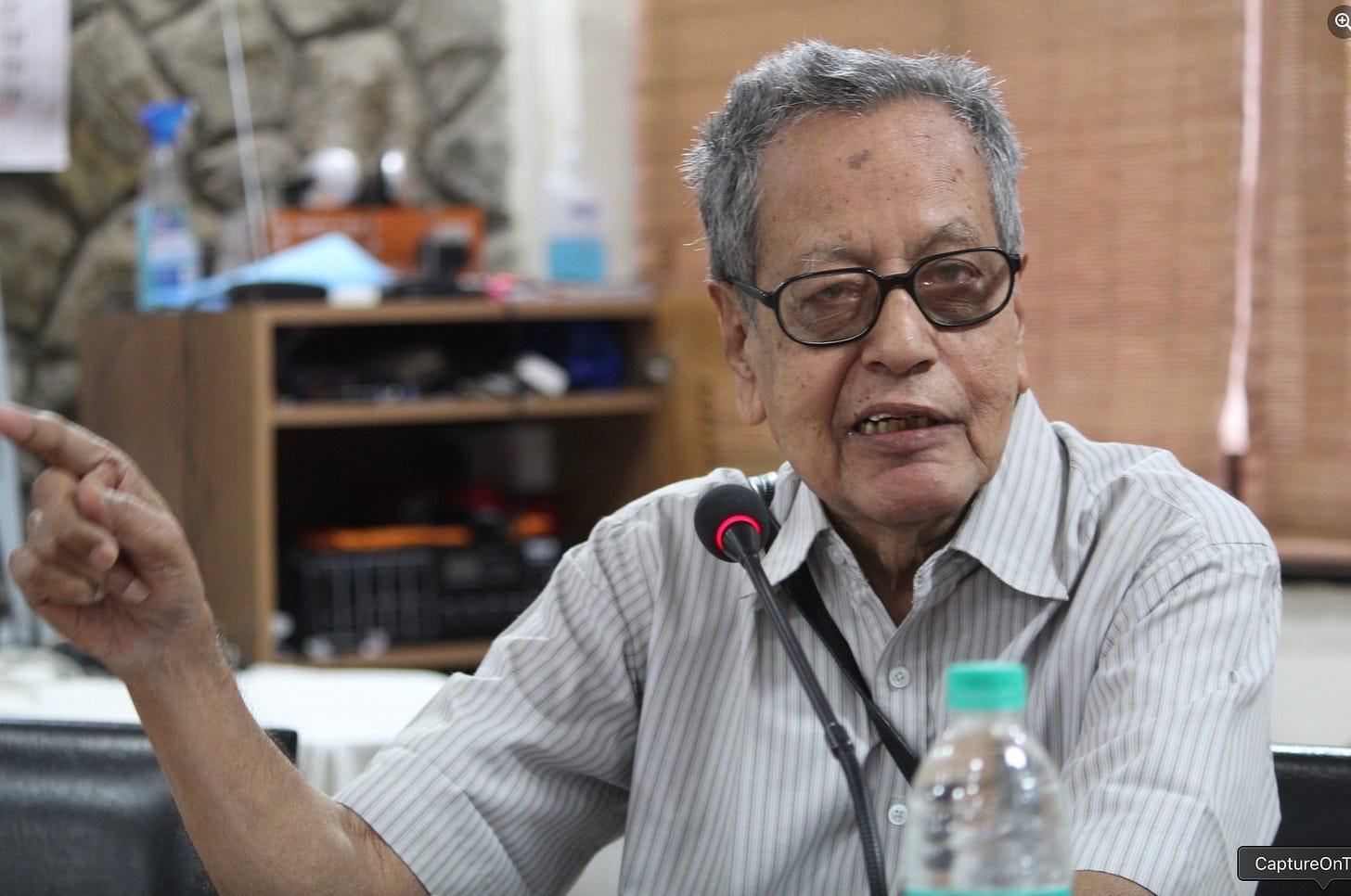

His last book "The Perilous Passage" is an outstanding piece of work, which is a must-read for every student of development. It is a masterpiece. This book is a regular feature in my courses. In 2016, I invited him to Mumbai to spend a day with my students and discuss the book. He gladly came, and we were joined by Professors J. Mohan Rao (UMass) and Sanjay Reddy (New School). It was an extraordinary day, with Amiyada admiring, agreeing, arguing and quarreling with the students and the other scholars (including his little quibbles with Irfan Habib!). The attached photo is from that day. And after the meeting, he said: "Ram, now, the adda". The Adda, as for every Bengali, was a must for Amiyada after an argumentative day. This was where he would unwind and let it go -- sometimes more informatively than during the day! He indeed reveled in it.

Something must be said about his body of work.

Amiyada was born in 1936. According to him, an event that disturbed him most in his childhood was his mother's death at the age of 30 due to complications in childbirth, which left him "with a lifelong anger at the treatment most societies meted out to women". No wonder then that all his work on development, particularly The Perilous Passage, were deeply concerned with women and health unlike other comparable texts.

He studied economics at the Presidency College, Kolkata and the University of Calcutta, and then went to Cambridge for a PhD. He would say that he was deeply influenced by four scholars during that period: Maurice Dobb, Richard Goodwin, Joan Robinson and Amartya Sen.

Inspired by his PhD, his first classic work came out in 1972 titled "Private Investment in India: 1900-1939". The standard argument from the "dyed-in-the-wool free traders" was that India's industrial backwardness was owing to "distorted foreign trade regimes". He responded in this book and showed that India's slow industrial growth under colonialism was because much of the investible surplus was either exported as a tribute, or used up in rentier consumption, or aborted because of the low propensity to invest in a poor and low-productive economy with sluggish demand for industrial goods.

Then, in 1982, came his next classic work titled “The Political Economy of Underdevelopment”, which was a fascinating attack on the neoliberal, free market explanations of continued underdevelopment in the former colonies. In his long review of that book, Terence Byres noted that the book was “a clarion call to revolution”; it filled a void in the development literature and stood tall alongside three other Marxist works: Paul Baran’s “Political Economy of Growth”, Maurice Dobb’s “Economic Growth and Underdeveloped Countries” and Geoffrey Kay’s “Development and Underdevelopment: A Marxist Analysis”. Byres was amused that Cambridge University Press published such an explicitly Marxist book -- given that most of their books were in the laissez-faire tradition -- and called it “a kind of dialectic justice”!

At this point, he was to write later, "history had...become part of my quotidian professional practice". And the uncovering of the "past in our present" was to continue till his last days. In the process, he became one of India's foremost economist historians.

In the 1980s, Bagchi immersed himself in another magisterial work, which was the writing of the history of the State Bank of India. Four volumes of this history were published in 1987, 1989 and 1997. In this work, he used enormously rich archival materials to analyse credit institutions and the operation of colonialism in India. This was the story of India's transition into a colonial economy but with financial institutions that actively favoured the imperial regime. B. R. Tomlinson was to remark in a review that just as the Presidency Bank enjoyed high rate of return on money, Bagchi's volumes had ensured that "their rate of return on intellectual capital is also high"! Even a Deepak Lal was to call it "Dr Bagchi's monumental endeavour"!

Bagchi’s work in the 1990s and after were focused on the catastrophic outcomes in Africa, Latin America, and partly Asia, of the stabilization and structural adjustment policies recommended and enforced by the IMF and the World Bank. This is the period where I have heard him directly and personally. He would get passionate and genuinely angry about the policy drift in the developing world towards more free market systems -- and also about what he would call "statistical massaging". This was where he would consistently speak about the East Asian developmental experience, and the role of the (developmental) state and society in directing and regulating the market forces there. He would powerfully argue that the reasons for the contrast between the East Asian success and the Indian failure lay in the role of nationalism, land reforms, and education in promoting the efficacy of state action in enhancing economic growth in East Asia.

In a later autobiographical description, Bagchi was to write: “my basic concern is still understanding the processes of reproduction of structures of inequality, and explaining how the same underlying processes lead to class formation and stratification along lines of gender, ethnicity, and locales of residence. I believe that theories of asymmetric and incomplete information, social externalities and sorting can provide some of the foundations of the Marxian theories of class and the Weberian theories of stratification. As a citizen of one of the poorest countries of the world, I am frequently sucked into various projects with political overtones. But I have not yet found much common ground with the dominant politicians bent on executing neoliberal policies while preserving an extremely unjust social order. The rise of Hindu fundamentalism to power in India has further exacerbated my conflict with the ruling elite...The themes of social and political conflicts and struggles of ordinary people to achieve a decent standard of living in dignity and freedom still form the core of my professional work. So long as the human world retains its unlovely constitution, my penchant for dissent is unlikely to disappear.”

This, overall, was a research project to which Bagchi did enormous justice throughout his long life of 88 years. He leaves no substitute behind, and his loss is an irreparable loss to the world of Marxism, of knowledge, and of dissent. And, of course, to the dream of a better world tomorrow.

Enjoy your adda with comrades in that world too, Amiyada. Good bye.